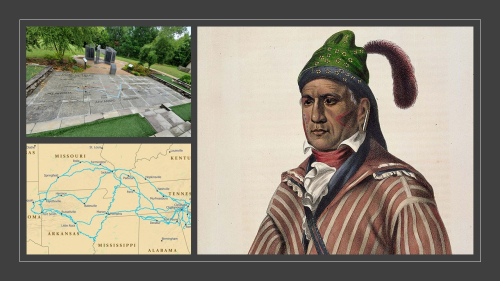

On October 31, 1837, approximately 311 Muscogee die in the steamboat Monmouth disaster on the Trail of Tears in the United States. All of these people were being forcibly removed from their ancestral homeland in the southern United States to the Indian Territory.

The direct cause was boat collision at night on the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

The U.S. Army had employed three steamboats to move the “Upper Creeks” band of Muscogee to the Great Plains.

There were 700 passengers on the Monmouth under poor navigating conditions. The Monmouth collided with a steamer towing a ship. The Monmouth was apparently violating traditional navigation rules and veered into the path of the other boat.

Dave Barnett, a Muscogee who gave one of the oral histories from the WPA Indian-Pioneer History project recorded in the 1930s, retold their experience of the disaster:

When we boarded the ship, it was at night time and it was raining, cloudy and dark. There were dangerous waves of water. The people aboard the ship did not want the ship to start on the journey at night but to wait until the next day. The men in command of the ship disregarded all suggestions and said, “the ship is going tonight.”

The ship was the kind that had an upper and lower deck. There were great stacks of boxes which contained whiskey in bottles. The officers in charge of the ship became intoxicated and even induced some of the Indians to drink. This created an uproar and turmoil.

Timbochee Barnett, who was my father, and I begged the officers to stop the ship until morning as the men in charge of the steering of the ship could not control the ship and keep it on it’s [sic] course but was causing it to go around and around.

We saw a night ship coming down the stream. We could distinguish these ships as they had lights. Many of those on board our ship tried to tell the officers to give the command to stay to one side so that the night ship could pass on by. It was then that it seemed that the ship was just turned loose because it was taking a zig-zag course in the water until it rammed right into the center of the night boat.

Then there was the screaming of the children, men, women, mothers and fathers when the ship began to sink. Everyone on the lower deck that could was urged to go up on the upper deck until some of the smaller boats could come to the rescue. The smaller boats were called by signal and they came soon enough but the lower deck had been hit so hard it was broken in two and was rapidly sinking and a great many of the Indians were drowned.

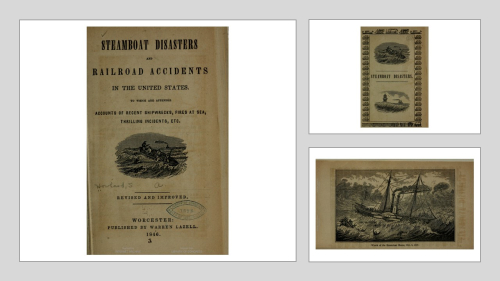

From:

p. 97 (#103)

LOSS OF THE STEAMER MONMOUTH,

On the Mississippi River, on her Passage from New Orleans for Arkansas River, October 31, 1837: by which Melancholy Catastrophe upwards of Three Hundred Emigrating Indians were drowned.

The steamboat Monmouth left New Orleans for Arkansas River, with upwards of six hundred Indians on board, a portion of the emigrant Creek tribe, who were removing west under direction of the United States’ government. In travelling up the Mississippi, through Prophet Island Bend, the steamer encountered the ship Trenton, towed by the steamer Warren, descending the river. It was rather dark, being near 8 o’clock in the evening, — and, through the mismanagement of the officers, a collision took place between the two vessels. The cabin of the Monmouth, shortly after, parted from the hull, drifting some distance down the stream, when it broke into two parts, and emptied all within it into the river. There were six hundred and eleven Indians on board, but three hundred of whom were rescued. The bar-keepers and a fireman were the only persons attached to the Monmouth who lost their lives. The disaster was chiefly owing to the neglect of the officers of the Monmouth. She was running in a part of the stream, where, by the usages of the river, and the rules of the Mississippi navigation, “she had no right to go, and where, of course, the descending vessel did not expect to meet her. Here is another evidence of the gross carelessness of a class of men to whose charge we often commit our lives and’ property.

9 ## p. 98 (#104)

98 STEAMBOAT DISASTE This unfortunate event is one in which every citizen of our country must feel a melancholy interest.

Bowing before the superiority of their conquerors, these men were removed from their homes by the policy of our government. On their way to the spot selected by the white man for their residence, — reluctantly leaving the graves of their fathers, and the homes of their childhood, in obedience to the requisitions of a race before whom they seem doomed to become extinct, — an accident, horrible and unanticipated brought death upon three hundred at once. Had they died, as the savage would die, upon the battle-field, in defence of his rights, and in the wars of his tribe, death had possessed little or no horror for them. But, in the full confidence of safety purchased by the concession and the compromise of all their savage chivalry, confined in a vessel strange to their habits, and dying by a death strange and ignoble to their natures, the victims of a catastrophe they could neither foresee nor resist, — their last moments of life, (for thought has the activity of lightning in extremity,) must have been embittered by conflicting emotions, — horrible, indeed: regret at their submission; indignation at what seemed to them wilful treachery, and impotent threatenings of revenge upon the pale-faces, may have maddened their dying hour.

COLLISION OF THE STEAMBOAT MONMOUTH AND THE SHIP TREMONT.

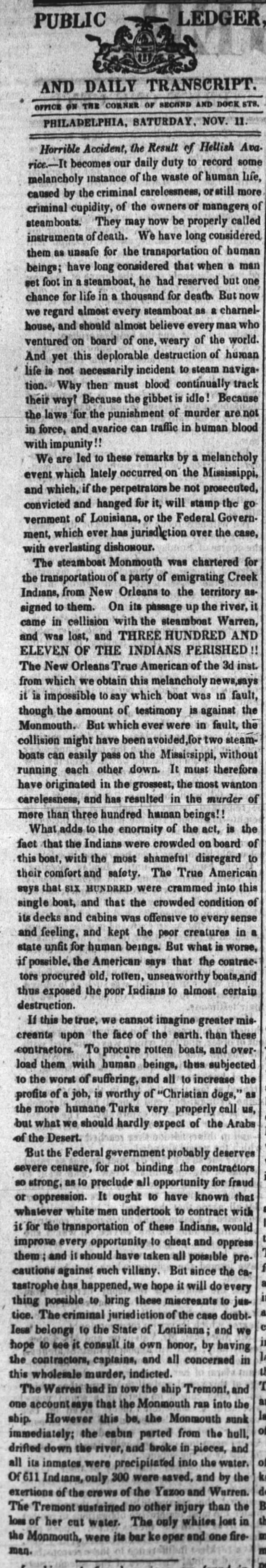

With strict propriety of language, we might call the awful catastrophe about to be particularized, a massacre, a wholesale assassination, or anything else but an accident. In some instances, and this is one of them, a reckless disregard of human life, when it leads to a fatal result, can claim no distinction, on any correct principle of law or justice, from wilful and premeditated murder.

The steamer Monmouth left New Orleans, October 231, 1837, for Arkansas river, having been chartered by the U. S. government to convey about seven hundred Indians, a portion of the emigrant Creek tribe, to the region which had been selected for their future abode. On the night of tile 30th, the Monmouth, on her upward trip, had reached that point of the Mississippi called Prophet Island Bend, where she encountered the ship Tremont, which the steamer Warren was then towing down the river. Owing partly to time dense obscurity of the night, but much more to the mismanagement of the officers of the Monmouth, a collision took place between that vessel and the Tremont, and such was the violence of the concussion, that the Monmoutli immediately sunk. The unhappy red men, with their wives and children, were precipitated into the water; and such was the confusion which prevailed at the time, such was the number of the drowning people, who probably clung to each other in their struggles for life, tbat, notwithstanding the Indians, men, women and children, are generally expert swimmers, more than half of the unfortunate Creeks perished. The captains and cre*s of the steamers Warren and Yazoo, by dint of great exertion, succeeded in saving about three hundred of the poor Indians, the remaining four hundred had become accusing spirits before the trihunal of a just God, where they, whose crimiual negligence was the cause of this calamity, will certainly he held acconntable.

The cabin of the Monmouth parted from the hull, and drifted some distance down the streatn, when it broke in two parts, and emptied its living contents into the river. The stem of the ship came in contact with the side of the steamer, therefore the former received but little damage, while the latter was broken up, to that degree that the hull, as previously stated, almost instantly went to the bottom. The ship merely lost her cut-water.The mishap, as we have hinted before, may be ascribed to the mismanagement of the officers of the Monmouth. This boat was running in a part of the river where, by the usages of the river and the rules adopted for the better regulation of steam navigation on the Mississippi, she had no right to go, and where, of course, the descending vessels did not expect to meet with any boat coming in an opposite direction. The only persons attached to the Monmouth who lost their lives, were the bar-keeper and a fireman.

It is not without some feeling of indignation, that we mention the circumstance that the drowning of four hundred Indians, the largest number of human beings ever sacrificed in a steamboat disaster, attracted but little attention, (comparatively speaking,) in any part of the country. Even the journalists and news-collectors of that region, on the waters of which this horrible affair took place, appear to have regarded the event as of too little importance to deserve any particular detail; and accordingly the best accounts we have of the matter merely state the outlines of the story, with scarcely a word of commiseration for the sufferers, or a single expression of rebuke for the heartless villains who wantonly exposed the lives of so many artless and confiding people to imminent peril, or almost certain destruction.

(source: Lloyd’s Steamboat Directory from 1856)

———————————

Trail of Tears art and poem

—————————————————————-

Thomas Barnett

Age 55, Tuckabatchee

Town(tulwa), Wetumka, Oklahoma

Billie Byrd, Field Worker

Indian-Pioneer History, S-149

June 24, 1937(vol. 13, pages 453-458)

Muskogee-Creek Removal

The Barnett name was Barnard before taking on the present way of pronunciation. Dave Barnett and Timbochee Barnett witnessed the mishap of the shipload of Muskogee-Creek Indians that were being brought to the new country from their old homes in Alabama and this is what Dave Barnett has told:

” When we boarded the ship, it was at night time and it was raining, cloudy and dark. There were dangerous waves of water. The people aboard the ship did not want the ship to start on the journey at night but to wait until the next day. The men in command of the ship disregarded all suggestions and said, “the ship is going tonight.”

The ship was the kind that had an upper and lower deck. There were great stacks of boxes which contained whiskey in bottles. The officers in charge of the ship became intoxicated and even induced some of the Indians to drink. This created an uproar and turmoil.

Timbochee Barnett, who was my father, and I begged the officers to stop the ship until morning as the men in charge of the steering of the ship could not control the ship and keep it on it’s course but was causing it to go around and around.

We saw a night ship coming down the stream. We could distinguish these ships as they had lights. Many of those on board our ship tried to tell the officers to give the command to stay to one side so that the night ship could pass on by. It was then that it seemed that the ship was just turned loose because it was taking a zig-zag course in the water until it rammed right into the center of the night boat.

Then there was the screaming of the children, men, women, mothers and fathers when the ship began to sink. Everyone on the lower deck that could was urged to go up on the upper deck until some of the smaller boats could come to the rescue. The smaller boats were called by signal and they came soon enough but the lower deck had been hit so hard it was broken in two and was rapidly sinking and a great many of the Indians were drowned.

Some of the rescued Indians were taken to the shore on boat

s, some were successfull in swimming to shore and some were drowned. The next day the survivors went along the shore of the Mississippi river and tried to identify the dead bodies that had been washed ashore. The dead was gathered and buried and some were lost forever in the waters.Timbochee, my father, at the time of the accident had a bag of money which he had brought with him from the old country. He reported that he had dropped it into the water. He afterwards gave this report to the officials on the following day of the accident. The officials recovered the bag which contained a great amount of gold and paper money. He kept the gold but he turned the paper money over to the officials who promised to dry them for him and return to him. This they did.”

Dave Barnett was buried in old Tuckabatchee town (tulwa) seven miles east of the present Hanna, Oklahoma.

TIMMIE BARNETT

Timothy (Tim or Timmie) Barnett was born of Tuckabatchee town (tulwa) and his father was Dave Barnett while his grandfather was Timbochee Barnett, also, of Tuckabatchee town (tulwa).

Tim Barnett was an educated man who lived in love for his tribal nation but was hated by some of the members of the tribe and nation that he loved, which was the Creek Nation. He was a willing hand to those who desired aid and he was called frequently by different towns (tulwas) to assist them to settle any matters or questions arising pertaining to Indians. He took it in his hands to make many trips to Washington for the benefit of his tribe, often paying for the expenses of such trips out of his own money as he was a man of wealth. He loved to converse as well as to ride horses, but above all things he loved to receive visitors and talk with them.

He lived with his wife, Hoketa Barnett, but he had another woman whom he claimed as his wife in the vicinity of the Greenleaf settlement southwest of the present Okemah, Oklahoma. A certain Seminole man began to take interest in and frequently visited and saw the woman at the Greenleaf settlement. This Seminole man began to boast, “I talk to his wife and he doesn’t even know it.” (This was in reference to the woman of the Greenleaf settlement and Tim Barnett.) It was not long afterwards that Tim Barnett learned of this as he went to the Greenleaf settlement and finding the Seminole man there, he killed him.

The Seminole Indians did not like the way in which one of their tribesman had been murdered, so they began to mobilize and were in readiness for a revenge. When the Seminoles reached the home of Tim Barnett, the Barnett clan of which there were a great number, were waiting for the Seminoles. It was then that a spokesman from the Barnett side defended the right that Barnett had in killing the Seminole man — stating that the Seminole man was trying to seduce the women of the Greenleaf settlement. This seemed to satisfy the Seminoles who very readily became on peaceful term with the Barnetts.

Tim Barnett, to show his gratitude, invited the Seminoles to spend the night with him before they returned to their homes and the Seminoles accepted. Tim Barnett ordered that a yearling be killed and prepared — this was done and everyone enjoyed the feast that was prepared.

Although the Seminole Indians seemed satisfied with the way things had turned out, but the Indian law was not satisfied so the lighthorsemen decided to have a regular trial. Tim Barnett was arrested and was being taken to Okmulgee. Some of the members of the lighthorsemen had such hostile feelings against Barnett that he was shot in the back and instantly killed. This act was against the orders of the Captain.

At one time, Tim Barnett, served with the Texas and McIntosh faction during the Civil War.

Tim Barnett was at the age of 65 when he died in 1872. He lived about two miles southeast of Wetumka, Oklahoma, and the only marked places of his old home are some plum bushes and the graves of two of his children.

The grave of Tim Barnett and that of his wife and another person (unknown) are marked by one large frame house, probably eight feet by twelve feet, Section 34, Township 9, Range 10.

Leave a comment